Review by Michael Beach

This work examines one of the large questions in the field of Science, Technology, and Society (STS). Are scientific facts discovered, or constructed? For the authors, facts are constructed.

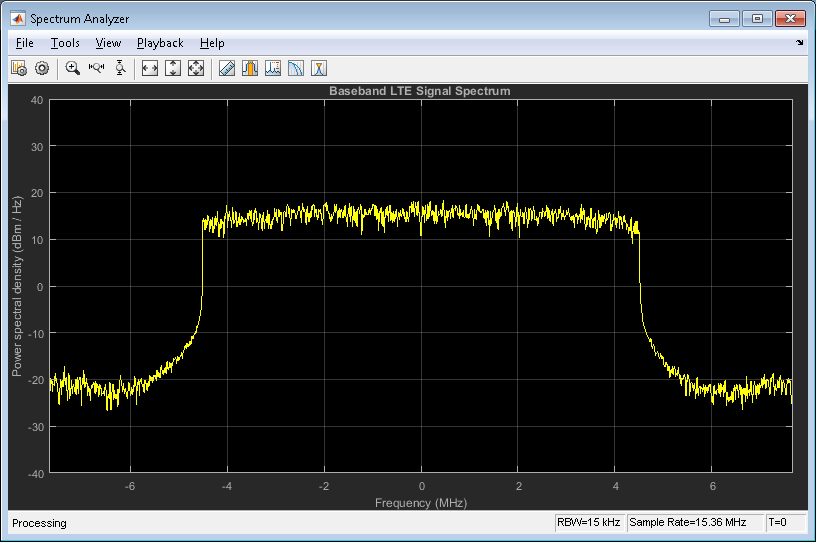

Among the ideas of this work, Bruno Latour and Steve Woolgar describe reducing disorder in data as lowering noise, or increasing the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) between data that support a specific hypothesis, and those that don’t. Data that don’t support a hypothesis are not necessarily counter-finding data, they are just not supporting data, hence noise. This is a concept I am very familiar with from my work in satellite and broadcast networking. It also directly relates to the authors’ concept of inscription. When data are created through process, the result is inscription. As theories become accepted they tend to change into tools to further test new theories. Tools can be physical machines or processes. When the machine or process become normalized they are said to be 'black boxed'. Such black boxes are no longer questioned, but are simply accepted. In labs, the machines (black boxes) referred to take information in and spit out printed material (data sheets or curves). It is the interpretation of data or curves that come to represent what matters in the argument for one idea over another. The more isolated one point of data is over others, the more distinct the information (higher S/N), and the more it supports a specific idea.

There are lots of steps along the way in the machine input, processing, printing, and transcribing of data into descriptive curves. Part of the work’s argument is that without all the manipulation a distinctive curve would not result. It is just as likely, the author’s say, that another set of complex manipulations could lead to a completely different looking curve, and a different conclusion. This is especially true if earlier curves had led to a different machine (black box) to process data in a different way.

My satellite and broadcast example includes the use of two tools. One is called a spectrum analyzer (SA), the other is called an integrated receiver decoder (IRD). Anyone who has ever worked with satellite or broadcast signals is familiar with these tools. In satellite, for example, after a transmit earth station (uplink) sends a signal to the satellite, and the satellite receives and sends the signal back to earth to a receive earth station (downlink), signal parameters can be both displayed by the SA, and made sense of by the IRD. Both machines have complex electronic systems within them. For example, the IRD has to first demodulate the radio frequency (RF) energy, then decrypt the data stream, then decode the information within the data stream, then transform the information into something a human can understand (audio, video, text). The SA similarly requires many parameter adjustments until the energy sent through the air can be displayed and measured in a standard format, typically comparing energy density levels at given frequencies (instantaneous or averaged over some period of time). Without all that effort the information does not really exist from the perspective of Latour and Woolgar. In fact, without the equipment, intelligence (audio, video, text) would simply be lost in space.

I’m reminded of basic communications theory. In order for communication to happen someone must have an idea, encode it (i.e. speech), and send it across a medium. The requirement does not stop there. Someone else must perceive the signal within the medium, and have the knowledge required to decode the information (shared language and context). Does the knowledge actually exist before all those communication steps are taken? Many in the field of STS would argue that knowledge not shared is not really knowledge. Chapter 5 of Laboratory Life emphasizes the need for a form credit in order to incentivize scientists to share or communicate findings, which in turn causes knowledge creation. This idea doesn't seem to sit well with Robert K. Merton's scientific norms, but are more akin to Ian I. Mitroff's counter-norms. Because of all the required inscription effort, the authors (Latour and Woolgar) argue that such knowledge is constructed rather than discovered.

Below is a typical SA plot. The square shape in the middle is the desired signal. The somewhat horizontally flat lines at either side are a representative measurement of the “noise floor”. There is never an absence of noise as radio frequency (RF) energy is always present everywhere. It is generated by the sun and many man-made devices. To obtain the S/N ratio is a simple comparison of the power measurement at a representative (average) frequency at the top of the desired signal as compared to power as measured at a representative (average) place in the noise floor. The two are then divided into a ratio. Depending on the sensitivity rating of the IRD in use, there is a minimum desired threshold. All measurements are in a decibel (dB) scale. Note the specificity of the measurement scales, as well as several 'settings' in the bottom right corner required to construct the graph. All of these scales and settings are adjustable within the black box of a spectrum analyzer. To Latour and Woolgar's point, changes in scales or settings (or principles and processes leading to creation of the SA) would yield data depicted differently on the plot.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed